At 1:52pm on August 23, my office began to shake. I saw the photos on the walls gently swaying right and left. Since my walls typically remain motionless, my brain had trouble making sense of what I was seeing. Construction, I thought? No, too much shaking. To cause that much motion, a machine would have to be digging below me, deep in the earth. Yes, in the earth. A tiny cartoon light bulb appeared above my head. That was it! Earthquake.

At 1:52pm on August 23, my office began to shake. I saw the photos on the walls gently swaying right and left. Since my walls typically remain motionless, my brain had trouble making sense of what I was seeing. Construction, I thought? No, too much shaking. To cause that much motion, a machine would have to be digging below me, deep in the earth. Yes, in the earth. A tiny cartoon light bulb appeared above my head. That was it! Earthquake.

Now that I had unearthed the cause, I didn’t know what to do. I quickstepped it through my undulating house. By the time I reached the living room, the shaking had stopped. I felt suddenly off balance – a sailor thrust off a boat onto dry land.

I flung open the front door. A nanny was standing on the sidewalk with a baby. “Did you feel that?” I asked. “I think it was an earthquake.”

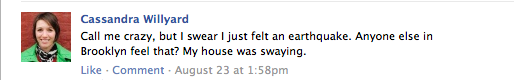

She hadn’t felt anything. Was I crazy? Maybe I had imagined the whole thing. I needed to find out. Google can be quite useful if you’re trying to find your friend in a city struck by an earthquake, but on this day Google failed me. I tried to call my husband, but too many callers had jammed the lines. That’s when I logged into Facebook and posted the following message.

The responses began almost instantaneously:

1:59 pm “yes”

2:02 pm “yes! I thought it was my neighbor upstairs walking too heavily”

2:02 pm “Happy birthday, I got you an earthquake!”

Had I looked at my news feed before posting, I would have realized that others were already talking about the quake. At 1:54pm a friend who works in lower Manhattan posted this: “Earthquake? Our entire building just started shaking. So California.”

Ok, so it really was an earthquake, but where?

At 2:04 pm, another New Yorker (and former Californian) posted a link to an abcnews.com article titled “5.8 Earthquake in Virginia felt in Washington, New York City, North Carolina.” (For an explanation of why people living several states away felt the shaking, go here.) Had I missed her post, I surely would have seen the response a friend in North Carolina sent me at that very same moment. “It was in Virginia – 5.8.”

Twelve minutes after the shaking began, I knew that I had experienced an earthquake, where the quake had occurred, and who else had felt it. Pretty damn impressive.

Here’s me again:

Once Facebook users had all their facts straight, they turned into comedians. At 2:24, a friend in DC wrote, “Things that aren’t affected by a 5.8 magnitude earthquake: Deadlines,” which garnered a “like” from me and 9 others. Another DC friend wrote, “Overheard in the office: Who wants to go looting?”

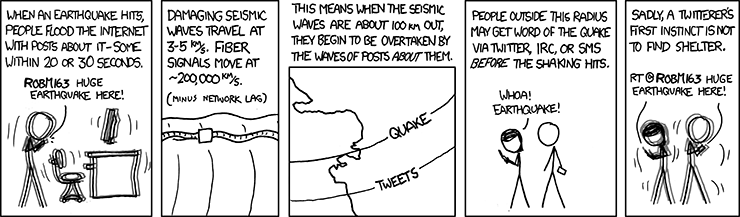

But the flurry of Facebook updates was nothing compared to what was happening in the Twittosphere. In fact, news apparently traveled so fast on Twitter that it outpaced the shaking. That means Twitter users far from the epicenter got the news before the quake began.

When I first heard this, I scoffed. My response was something like, “That’s bullshit!” But is it?

When I first heard this, I scoffed. My response was something like, “That’s bullshit!” But is it?

Wired blogger and physicist Rhett Allain did the math. His verdict? “If you are farther than 230 km from the center of the earthquake, you might be able to get a tweet about the earthquake before you feel it.” New York lies 451 kilometers northeast of the quake’s epicenter, near Mineral, Virginia, and 329 kilometers northeast of DC, where many of the tweets likely originated. So I stand corrected.

SocialFlow, a company that helps other businesses make use of social media (I think that’s what they do), developed a really amazing interactive map showing how the tweets spread. On the company blog, a VP notes, “Within seconds of the earthquake hitting VA, we see hundreds of people across the States passing information. There’s a clear 40-50 second warning signal between the very start and the New York City region. This signal manages to reach tens of thousands of people before a minute is over, in effect, a network of human sensors that not only identifies a substantial event, but also passes on information in remarkable ways.”

Twitter’s developers have already tried capitalize on the site’s apparent ability to predict earthquakes in this hilarious video.

Whether or not you believe Twitter can be used as an earthquake warning system, it clearly works as a tool to rapidly disseminate important information. The number of tweets during the earthquake and its aftermath hit 5,500 per second — a total of 40,000 tweets in the first minute alone. I guess this social media junk is good for something after all. Does anyone know if there are serious efforts to harness the power of Facebook or Twitter for natural disaster preparedness? And are researchers using the sites? Is the information freely available for data crunching? Anybody else have an example of Twitter or Facebook’s usefulness during a natural disaster?

**

Image credits

Photos askew on a wall courtesy of Bethany L King on flickr.

Comic courtesy of XKCD.

The 18th century brick building I work in jiggled a bit and then I swear, it moved from side to side. The hanging lights certainly moved. I diagnosed earthquake immediately (I’ve written about them a lot) and got onto USGS’s website. Yes, there was an earthquake. How big? where? USGS wasn’t telling me that but meanwhile the guys in the next office are yelling out mag.6! Virginia! How did you know that, I said. They yelled back, Twitter! Oh. Dumb me. A little learning can make you dumb.

Danger Room reported on an IARPA program that’s aiming to do just that– mine social networks for signs of the next tsunami. “Open source intelligence” is what they’re calling it.

http://www.wired.com/dangerroom/2011/07/spies-tweets-tsunami/

Cassie — I think the Pacific Coast has something a little more archaic for tsunami warnings. They use telephone trees!

Of course, the problem is if you have a natural disaster (hurricane, tsunami, earthquake) that does real damage, it will probably wipe out electricity and/or the internet.

I had better luck with Google that day. I entered “earthquake,” and the top hit was: earthquake.usgs.gov. Which gives real-time information on earthquakes. So I knew that a 5.8 earthquake had occurred in Virginia “five minutes ago” (or whatever it was). Just now, for instance, I went to that site and learned that: one, Tonga had a 6.3 two days ago; two, there is a place called Tonga.

Ushahidi makes software for crisis-mapping that mines text messages and social media feeds. I’m not sure if it can be used for disaster preparedness, but I understand that groups have found it useful for planning rescue and recovery efforts.

http://www.ushahidi.com/about-us/newsroom/in-the-news