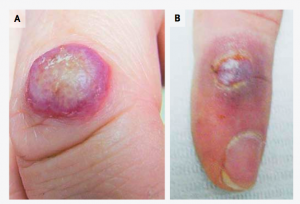

On a crisp fall day in November 2008, a wildlife biologist killed a deer in Eastern Virginia. He slit the carcass open from breast to tail and removed the animal’s internal organs. Hunting knives are very sharp. And, in the process of field dressing the deer, he nicked his knuckle. I imagine he didn’t think much of it at the time. But the cut did not heal. Two weeks later he had a painful bump where the wound had been. By mid-December, the bump had become an angry purple nodule. Not surprisingly, he sought medical attention.

On a crisp fall day in November 2008, a wildlife biologist killed a deer in Eastern Virginia. He slit the carcass open from breast to tail and removed the animal’s internal organs. Hunting knives are very sharp. And, in the process of field dressing the deer, he nicked his knuckle. I imagine he didn’t think much of it at the time. But the cut did not heal. Two weeks later he had a painful bump where the wound had been. By mid-December, the bump had become an angry purple nodule. Not surprisingly, he sought medical attention.

The doctors sliced off the nodule and sent it to the laboratory for testing. They gave the biologist an antibiotic, but the laboratory technicians couldn’t find any evidence of bacteria in the violet slice of knuckle skin. Nor did they turn up any fungi. Nevertheless, the man’s wound seemed to be healing.

In January 2009, however, the bump came back. A new nodule appeared adjacent to where the first one had been, growing larger each day. Again, the doctors removed the lesion and sent it to the lab. The pathologist thought it looked a bit like a sore caused by orf, a viral disease that affects mainly in sheep and goats. Orf can affect humans too, but the biologist told his doctors that he hadn’t been around any sheep or goats.

Meanwhile, a hunter in Connecticut was going through an eerily similar ordeal. He too had recently nicked his finger while field-dressing a deer. He too developed the angry purple nodule. He too sought medical care.

That’s when the physicians—both those in Virginia and Connecticut—decided to enlist the help of detectives at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). They sent samples of the men’s purple knuckles to CDC headquarters in Atlanta. (Regular parcel post? Or is there some sort of separate system for shipping unnaturally colored knuckle skin potentially teeming with virus? Not UPS, surely. They wouldn’t even let me ship a small box of cheese).

In late December, the CDC reported what it had found in the men’s frightful fingerskins: a new parapoxvirus. Parapoxviruses cause lesions in cows, sheep, goats, and red squirrels. In fact, orf—that oddly named disease that it looked like but wasn’t—is caused by a parapoxvirus. But never before had a parapoxvirus been uncovered in white-tailed deer. (The last new parapoxvirus (identified in 1995) was found in red deer in New Zealand, so the deer connection wasn’t a total shock.)

The good news is both men fully recovered. And the virus doesn’t appear to cause disease in deer. The bad news—the downright depressing news—is that this is likely the tip of the (mostly undiscovered) pathogen iceberg that lies hidden in the wilds of our planet.

The story reminded me of a TED talk I heard last year by Nathan Wolfe, a virus hunter and expert in emerging infectious diseases. He talked about the intimate connection between hunters and their prey. During the butchering process, the two may even exchange blood, as in the case of the deer hunters. And what better way to share viruses than to share blood? In fact, one predominant theory suggests that HIV arose when hunters in Africa contracted a closely related virus while butchering chimps. Who knows how many more incipient HIVs are lurking in the African bush? Frankly, Wolfe’s talk scared the bejeezus out of me.

But there is a (modest) bright side. The explorer part of me, the part that is not terrified of unknown viruses, sometimes gets depressed. Every remote corner of this planet has been trod. Perhaps, I think, there is nothing left to be discovered. That may be true if we’re talking about large mammals, but when it comes to bacteria and viruses, I couldn’t be more wrong. “This is honestly the most exciting period ever for the study of unknown life forms on our planet,” Wolfe said. Our world is teeming with microbes. “The dominant things that exist here we know almost nothing about. And yet finally we have the tools which will allow us to explore that world and understand them.” Now if only someone would let me into that Ugandan bat cave where they keep all the Marburg virus . . .

**

Image credits: The deer photo is from the USDA’s Scott Bauer. The image of the angry purple nodules on the hunters’ fingers is courtesy of the New England Journal of Medicine.

Great article, and if you recall, this was also a big concern with WWD, but as far as I know they haven’t found a case where it has been transferred. Thanks for sharing this.