This has been a bad year for contrarian cosmology. First Geoffrey Burbidge died, at the age of 84, on January 26. And now comes the news that Allan Sandage, also 84, died last Saturday.

I’ll let other obituaries explore Sandage’s monumental scientific biography at length and in depth: apprenticing under Edwin Hubble; assuming Hubble’s observing program after his death in 1953; recalibrating the distances to galaxies and, therefore, the scale and age of the universe; compiling the Hubble Atlas of Galaxies; making the first observation of a quasar; collaborating on a paper positing the formation process of the Milky Way. He was the last of the lone astronomers, those gods of Mounts Wilson and Palomar, doing daily battle with the abyss. Sandage once defined cosmology as “the search for two numbers”—the current rate of the expansion of the universe, and how much that rate is changing over time. Know those numbers, he declared, and you would know the alpha and the omega of the universe: its age and its fate.

For me, though, his death also brings to mind a quieter, less celebratory subject that has nagged at me for years: the relationship between individual psychology and the scientific method.

I met Sandage only once, when I visited him in Pasadena for a profile I was writing for the New York Times Magazine. Three days earlier, on May 25, 1999, NASA had held a press conference in Washington to announce that the Hubble Space Telescope Key Project had derived a value for the Hubble constant—the first of Sandage’s two numbers. The current expansion rate of the universe, the Key Project concluded, was 70 kilometers per second per megaparsec, a value that would put the age of the universe at 12 billion years. Sandage, however, had spent nearly half a century pursuing the same goal, and the answer he had gotten was in the mid-50s, or an age of 15 billion years. It was an answer he had gotten again and again and again; it was one he had continued to get long after other astronomers using a host of methods had determined that the value was likely to be significantly higher. The purpose of the Key Project was to use the Space Telescope to do what even the most powerful Earthbound telescopes couldn’t: answer the question once and forever. And the astronomers on the Key Project did. They got their answer. But what that answer meant, as everyone in astronomy knew, wasn’t simply that the universe was expanding at the rate of 70 kilometers per second per megaparsec. It was that Allan Sandage was wrong.

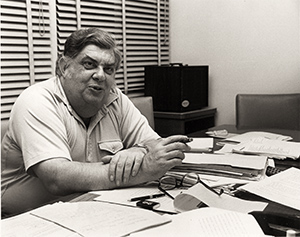

”It’s a psychological disaster,” he told me when I stopped by his office at the Carnegie Institution observatories’ headquarters in Pasadena. “I mean, you just can’t imagine what the last two weeks have been like.” Then he said something that he would repeat at least half a dozen times over the next two days: “If you permit it, the world will either break your heart or turn your heart to stone.”

In Sandage’s case, I suspect, the world did both. But did it have to? Did he permit the world to do its worst? For him, the “psychological disaster” wasn’t that he’d gotten the wrong answer. Nor was it that the astronomy community was embracing what he considered to be the wrong answer. It was that the astronomy community was recklessly discarding his own decades of effort that had resulted in the right answer.

“The answer will come,” he once said (in Dennis Overbye’s Lonely Hearts of the Cosmos), “when responsible people go to the telescope.” To his way of thinking, Wendy Freedman, the director of the Key Project, was one such irresponsible person. All she wanted, he told me, was “fame.” Even though her office was just down the hall and around the corner from his, Sandage refused to speak to her. And this behavior was typical. Sandage routinely cast aside colleagues and acolytes he felt had betrayed him, only because they had gotten the “wrong” answer. If private correspondence of his that I’ve seen is any indication, he knew this behavior was a function of his own personality, but he couldn’t stop himself.

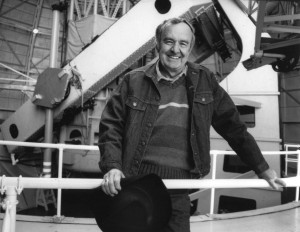

Even so, Geoffrey Burbidge considered Sandage “very conventional.” Burbidge was one of the last of professional astronomy’s Big Bang skeptics, a coterie that preferred the Steady State theory. “I call us the Elderly Radicals,” he told me in 2002, when I interviewed him for a profile in Discover. Burbidge and I were sitting in the same oceanfront restaurant in La Jolla where he and Sandage sometimes met for dinner; they spoke on the phone two or three times a week. “I’m always telling him to join the Elderly Radicals,” Burbidge said. To him, the Big Bang was nothing but a “bandwagon,” a fashionable theory that was popular because it spoke to “a religious belief. People want a beginning.” Like Sandage, Burbidge had spent a lifetime performing brilliant astronomy, yet his reputation increasingly had little to do with the science itself. “People don’t like you to be nasty, you see,” he said. “People don’t like people who disagree with them as much as people who agree with them. Most people like to get along in life by being nice. It’s easier to be nice than to be truthful.”

Even so, Geoffrey Burbidge considered Sandage “very conventional.” Burbidge was one of the last of professional astronomy’s Big Bang skeptics, a coterie that preferred the Steady State theory. “I call us the Elderly Radicals,” he told me in 2002, when I interviewed him for a profile in Discover. Burbidge and I were sitting in the same oceanfront restaurant in La Jolla where he and Sandage sometimes met for dinner; they spoke on the phone two or three times a week. “I’m always telling him to join the Elderly Radicals,” Burbidge said. To him, the Big Bang was nothing but a “bandwagon,” a fashionable theory that was popular because it spoke to “a religious belief. People want a beginning.” Like Sandage, Burbidge had spent a lifetime performing brilliant astronomy, yet his reputation increasingly had little to do with the science itself. “People don’t like you to be nasty, you see,” he said. “People don’t like people who disagree with them as much as people who agree with them. Most people like to get along in life by being nice. It’s easier to be nice than to be truthful.”

What the world saw as stubbornness or even cruelty, Sandage and Burbidge saw as rectitude. Which brings me to my nagging questions about the relationship between psychology and science.

Is a constitutionally contrarian nature what drives people like Sandage and Burbidge to their unpopular convictions? Do they unconsciously want to be different, so they adopt extreme and unpopular positions? Do they find deliverance in their martyrdom?

Or is the unpopularity of their convictions what leads them to don a contrarian carapace? Do they weigh the evidence, reach unpopular conclusions, and (deep breath) go for it? Does their ostracism emerge as an unfortunate byproduct of defending what they believe they have to defend?

Either way, what effect does their contentiousness have on the reception of their data? Does their take-no-prisoners attitude make their convictions more unpopular in the community than a rigorously scientific evaluation of their work would merit?

I can’t answer these questions. I don’t know that there are answers. What I do know is that both a Hubble constant around 70 and the Big Bang theory are here to stay, at least until something better comes along. As Max Planck once wrote: “A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.”

R.I.P. Allan Sandage and Geoffrey Burbidge. Also, a Hubble constant of 55 and the Steady State theory.

* * *

Images: Sandage (upper), Carnegie Institution for Science; Burbidge, NOAO/AURA/NSF.

I think your questions are interesting and have wondered about them myself — to what extent is any given scientific controversy being driven by the cussedness of one or two people? Sandage was my #1 case study, but I have others. I wonder how often it happens, and whether it happens in fields other than cosmology (especially in fields with actual and plentiful data), and to what extent it undermines the march of science.

That said, Sandage was as smart as they come, and both outsized and open about his own humanness, and I was entirely fond of him. I miss him being out there rampaging around.

The flowerbed of science is fertilized with dead and decaying ideas, from surface soil to bedrock. The current crop dies one day, too, and new ideas will blossom and face the sun on the backs of that freshly mulched nonsense.

But it’s the obstinate ideas, buried by the onward and upward, that give new roots something to anchor onto. The next big idea is just drifting free in nitrogen-rich bullshit unless it’s pitted against something stubborn and unmoving.